(This article is also found here: https://mises.org/wire/inverted-yield-curves-recessions-and-you)

If one

reads the headlines you might think that since the yield curve has inverted,

the economy is in a recession, Trump will be swept from office and then the

Progressives’ goals are right around the corner. Not so fast!

While much of that may still happen, we are not there yet.

While

some on the Left may

be openly hoping for the economy to slip into a recession, we are not currently

in a recession and whether we are heading for one requires some serious economic

analysis. To understand what an inverted

yield curve means, we first need to understand what the yield curve is.

What

is the Yield Curve?

Often,

when economists think of the economy, they simplify. This action is necessary. They try to focus on the important factors

and set the less important and irrelevant factors aside. Thus, a theory of how the economy works is an

abstraction that tries to illustrate causal and connected links.

In

many economic models, economists use a single interest rate to represent the

whole intertemporal market. Often they

will theorize that when the interest rate rises, X will

happen or if the Fed lowers the interest rate, then Y will be

the result. However, the real world does

not have a single interest rate. In

fact, there are many interest rates.

When we separate interest rates across maturities, we get what is called

“The Term Structure of Interest Rates.”

So across this structure, there will be an interest rate for a 3-month

instrument, another interest rate for a 1-year instrument, a different one for

a 10-year instrument, and so forth.

When

we look at a very specific type of term structure, where the default risk is at

zero, we are looking at what is called “The Yield Curve.” In the US economy, there is really only one

market where we find zero default risk and that is the market for US Treasury

Bills, Notes and Bonds. The reason why

there is zero default risk is that if you go to cash in your US Treasury Bond,

you will always be able to get dollars.

Since the dollar is fiat money, meaning that it is not backed by gold,

the US government can always create more dollars to honor its obligation. (Of course the value of the dollar will be

eroded by the money creation, but that’s a different story.)

If we

plot out the different maturities across the horizontal axis and the percentage

rate of returns on the vertical, then we will have a graphical vision of the

Yield Curve. Typically, the short-term

rates are lower than the long-term rates.

Graphically, we would see an upward slope. There are two major reasons for this: inflation

risk and liquidity preference. Inflation

risk is the risk that stems from the fear that the value of the dollar will

depreciate over time. As we look at the

historical inflation rates we see that the value of the dollar has been

continuously eroded since we left the gold standard. Liquidity preference stems from an uncertain

future. (See Figure 1.)

An

investor might reason in this way, “I want to invest my money, but what if

something happens and I need cash?” This

reasoning reflects the fact that it is better to be liquid than not. When we add a term structure to the

investment, we see that this risk changes over the various time horizons. So what is the risk of something happening where

I will need cash in the next 3 months?

Now compare that risk with tying up money for one or two years. Then compare that risk with tying up money

for 30 years. As the length of maturity

increases, the risk of something unexpected happening also increases. Thus, as we look further into the future, we

see a higher degree of compensation to cover this ever-increasing risk.

So while

there are different segments along the yield curve, each segment is not

independent from other segments. This

interconnection comes from arbitrage. If

an investor is able to make more money in one segment, he can easily sell in

one area and buy in another. Thus, the

yield curve is interconnected through supply, demand and arbitrage. An inverted yield curve is where the

short-term rates are higher than the long-term rates, i.e., it is downward

sloping.

Where

are we now?

Is

it true that the yield curve has inverted?

The answer to this is like many answers in economics, it is both a “Yes”

and a “No”. On August 5, 2019, the daily

rate of the 10-year bond fell to 1.75%, while the 1-year bond rose to

1.78%. (Incidentally, the 2-year bond,

which the press was talking about, has not closed above the 10-year rate between

August 1 and August 26, 2019.) According

to the US Treasury, the 1-year bond has closed above the 10-year bond every day

since August 5th, but the largest gap has only been 0.21%. Additionally, the 10-year rate has closed

less than the 3-month rate every day since the middle of May 2019 (with the

lone exception of July 23, 2019). So

right now, I would say that the yield curve is flat, but it has been trending

toward an inversion for quite some time.

Why

does any of this matter?

If we

look at the monthly data, we see that prior to every recession since 1955, the

yield curve inverted four to six quarters prior to the onset of the recession. See Figure 2.

In Figure 2, the yellow vertical

bars represent recession. The lines are

the differences between the various long-term rates (10, 20 and 30 years) and

the two short-term rates (3 months and 1 year).

When the difference falls below zero, the yield curve has inverted.

Now the real question is whether there are any false

positives, where the difference is less than zero and there is no yellow bar. The answer is yes, there was one in 1966-67. However, depending on which dataset one looks

at, there was either one quarter of negative growth (or nearly negative) in

1967. Recessions are typically

categorized by at least two quarters of negative growth and so I believe that

the relationship holds.

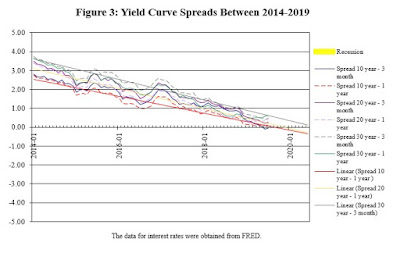

If we take a closer look at the

yield curve spread and add some straight line projections, we get Figure 3.

What we see here is that whole

curve is flattening. Furthermore, if

everything continues along these straight lines (which never actually happens)

we should expect to see the yield curve truly invert around October or November

of 2019. And if history follows the

past, we should then expect to see the economy in a recession 4 to 6 quarters

later, meaning that somewhere between October 2020 (around election time) and

April 2021, the economy will be contracting.

Is

this a fait accompli? Is this story

written in stone? By all means,

“No.” History may rhyme, but it is not

fatalistic. To understand where we are

headed, we need two things, the facts and, secondly, the context within to put

the facts in order to understand them.

In other words, we need some data and a theory.

The

Data

To start,

we will take a look at the monthly rates of US Treasuries from 1953 until August

2019. See Figure 4.

Figure 5 shows a close up view

between 2003 and August 2019.

What we see is that while the

long-term rates have come down a little bit, it is jump in the short-term rates

has flattened and may eventually invert the yield curve. It appears that by 2016, the increase in

short-term rates was well underway.

The next

question that we should be asking is, “What is it that is driving up short-term

rates?” In order to find the answer, we

first need to know where to look and that knowledge comes from economic theory.

The

Theory

In

2004, I finished my dissertation examining

the relationship between the yield curve and economic downturns. What I found is that this is a very complex

relationship. The reason why short rates

are changing is simply due to changes in supply and demand. The difficulty lies

in tracing those root causes of these changes.

In order for the short-term rates to climb, there must either be a

decrease in the supply of loanable funds, an increase in the demand for

loanable funds, or a combination of both forces.

Is there

a decrease in the supply of short-term funds on the market? While the Fed has been engaged in some

monetary tightening, interest rates have been at historically low levels since

2008. (Take another look at Figure 5

above and focus on the short-term rates between 2009 and 2016.) Furthermore, in July the FOMC (the Federal

Open Market Committee sets the targets for short-term interest rates) officially

reversed course and announced lowered the targeted rates from the 2¼ – 2½%

range to the 2 – 2 ¼% range. So, it is

safe to say that it rise in short-term interest rates is not really a function

of tightening supply. Thus, it must be a

function of demand.

The

question we need to next investigate is, “Why is there more demand for

Short-term Loanable funds?” It is here

that things become complex. We must

first start with the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT).

The ABCT

says that economic recessions can be caused by an expansion of artificial

credit. This expansion leads to relative

decrease in the interest rate (yes, we are assuming a single interest rate

here). The relative decrease in the

interest rate will cause several things.

First, it will cause a shift from savings towards consumption. Secondly, it will not simply cause an

increase in investment spending (overinvestment), but it will also cause a

misdirection of the capital spent (malinvestment).

As the

credit expansion follows its course, it causes an artificial economic

boom. During the boom, there is

expansion throughout the entire economy, however there are concentrations in

two particular sections of the economy: the early stages and the final stages

of the production process. The early

stages are where we are clearing land and pouring concrete foundations. As a result, if we make a mistake, these can

become very costly. The final stages of

economic production are those closest to the consumers. While these later stages are also subject to

the business cycle, the severity of fluctuations at these stages are less than

those of the earlier stages.

In my

dissertation and in a subsequent article, I

argue that as we near the peak of the economic expansion, profit margins will

be squeezed by rising input prices. As

input prices climb, businesses will seek short-term financing to complete their

projects.

An

Illustration

Suppose

that you are a home builder and the interest rate stands at 6% (as it did in

2001). You have looked at the market and

expect the return on your building and selling of homes will yield a 4% rate of

return. Of course, you do not put your

money into this project.

Now

suppose that the interest rate has fallen from 6% to 1% (as it did in

2003). What will you do? If you do nothing, your competitors will

leave you standing in the dust. You must

keep up with your competitors and thus you choose to invest. Suppose that while you want to make 6 houses,

there are only enough bricks for 4. Can

you start 6 foundations? Yes, of

course. No one in the economy really

knows how many “bricks” (available resource inputs) exist in the current and

near future economy. And so as an

entrepreneur, you follow the market signals and start 6 foundations. As you and your competitors start to use the

bricks, the price of these bricks starts to climb. As the price of bricks climbs, the funds at

your disposal no longer cover the costs of completing the 6 houses. Without getting the bricks, the houses will

remain incomplete and the project will be a huge loss. It is imperative that your company gets those

bricks. And so your home building

company is willing to borrow short-term money at higher and higher rates in

order to complete something and reap at least a little return from the project.

Back

to the Data

So

according to the theory outlined above, we are positing that the interest rates

are climbing in the short-run because of input price increases, which are

squeezing profit margins. So, the next

step is to look at input prices.

Unfortunately, the data that is collected by US governmental

institutions were designed from a Keynesian perspective. Thus, the data that an Austrian would like to

look at doesn’t really exist, at least not in a format that we would prefer. Nevertheless, there are some general statistics

that we can use. I have pulled six

statistics from the Federal Reserve Economic Data which pertain to commodity

prices: PPI: All Commodities, Global Price Index of All Commodities, PPI:

Construction Materials, PPI: Construction Machinery, PPI: Iron and Steel, and

PPI: Plastics and Synthetic Rubber.

If

we look at the short-term interest rates in Figure 5, we see that they start to

climb in 2016. What does tracking these commodity

prices from 2016 through 2019 show us?

In each category we see prices rising, just as the theory predicts. Furthermore, if we look three years before

2016 and examine the range between 2013 and 2016, what do we see? As summarized

in Table 1 below, in four of the six categories, the prices were falling. The two categories were the prices were

increasing (PPI: Construction Materials and PPI: Construction Machinery), we

see that the rate of increase has accelerated after 2016.

Table 1

|

Annual Percent Change

2013 - 2016

|

Annual Percent Change

2016 – 2019

|

PPI: All

Commodities

|

-3.40%

|

+2.77%

|

Global

Price Index of All Commodities

|

-23.01%

|

+9.81%

|

PPI:

Construction Materials

|

+0.48%

|

+3.15%

|

PPI:

Construction Machinery

|

+1.45%

|

+1.79%

|

PPI: Iron

& Steel

|

-8.97%

|

+6.75%

|

PPI:

Plastics and Synthetic Rubber

|

-7.50%

|

+2.96%

|

What

should we look for next?

The

takeaway from the analysis so far is that we are coming to the end of an

economic boom and nearing the upper turning point of the business cycle. The next phase in the business cycle is

business failures and bankruptcies.

According to the ABCT, the areas that we should be looking for

bankruptcies are in the early stages of production.

There are

some signs that bankruptcies are increasing.

We can see that there is a lot of economic distress in the farming

sector, but this might be more the result of the trade tariffs than the normal

course of the business cycle. The

Chinese know that a lot of political support for President Trump lies within

the agricultural community and so they have specifically targeted their trade

tariffs on this constituency group.

The

overall point is that the data is not yet clear. In fact, it is probably a little too early in

the business cycle for a disproportionate

amount of bankruptcies. Bankruptcies

occur all the time, in both good and bad economic times. So, as the yield curve inverts over the next

several weeks or months, we should expect to see a steadily rising amount of

bankruptcies until we make the turn and the bottom falls out.

What

can be done to mitigate the next recession?

Many

people believe that the higher you go, the greater the fall. When it comes to business cycles, it is

simply not the case. We can have a small

upswing and a dramatic collapse, a large upswing followed by a mild recession,

or anything in between. The key market factor

in determining the level of economic decline is the amount of savings. Simply put, the larger the amount of savings,

the smaller the downturn will be. Thus,

anything that can be done to stop discouraging savings should be done. This is not to say that government should

force savings to occur, but every policy where the government is currently

encouraging spending over savings should be stopped. For example, when the government decides to

increase spending to stimulate consumption, it is shifting funds that would

have been otherwise saved into spending.

The policies that the government enacts during the downturn will

strongly affect the size and duration of the collapse. Misguided policies, such as stimulus

spending, actually prolong an economic downturn and delay a full recovery.

Nevertheless,

there are steps we can take that encourage savings. Here are three examples. First, we can cut the capital gains tax. Savings are actually deferred

consumption. Since retained earnings are

a form of deferred consumption, they are a type of savings. So any policy that taxes or discourages

retaining earnings should be abolished.

Secondly, if the US changes from the income tax to a consumption tax,

there would be a disincentive to spend and thus a relative incentive to

save. And third, if the US Federal

Government balanced budget by cutting spending, there would be an encouragement

of savings. Currently, the US Federal

Government is borrowing money to finance its spending. These “saved” funds are not actually saved,

but spent by the US government. By

cutting the amount that the government spends, these funds will shift back into

the private sector as investment funds.

Furthermore

there are some additional steps that we could take to mitigate the

recession. First, we need to recognize

that the artificial bubble was caused by the expansion of the money

supply. We need to stop this inflation. Denationalizing and deregulating the money

supply would be a step in the right direction.

Secondly,

we could make the bankruptcy process easier.

The way in which we turn a recession into a recovery is by clearing out

the misaligned capital structures and converting the malinvestments into proper

investments. In the last downturn, the

Federal Government bailed out General Motors.

Suppose, instead, what would have happened if it did not bail out GM. GM would have gone bankrupt. It would have had to sell its assets to generate

cash to pay its creditors. Thus, GM

would have had to sell Cadillac and Corvette.

Of course, Cadillac is not worth zero dollars. There would be buyers for Cadillac, maybe

Ford or Toyota or Elon Musk. Whoever the

ultimate buyer would be, that buyer would not have to pay top dollar for

Cadillac (it is a going-out-of-business sale).

This new owner could then, on the very next day, turn on the very same

machines, produce the very same car, and sell it at the very same price. However, this new owner would be able make a

profit where old GM could not. Why? It is because this new owner has a lower cost

structure. The new owner bought the capital

in a fire sale. This process is how we

convert a recession into a recovery.

Thus, by making the bankruptcy process easier and faster, the economy

can realign itself more quickly. If we

continue to follow this logic, if we also make mergers and acquisitions easier,

we can reduce both the depth and the duration of the recession.

Many

people have claimed that the Austrian approach leads government officials to

“do nothing” in the face of a recession.

When the people are clamoring for “something to be done” the Austrians

say, “No.” But this this is simply an

empty charge. Outlined above are several

positive steps that can be taken to reduce the size and scope of the

recession.

I do not

know when we will reach the upper-turning point and start the economic slide

into recession. From this analysis, I

can say that it is coming. If history

follows the same path, then sometime between October 2020 and April 2021, we

should be in a recession. The questions

of how long it will last and how deep it will get depend upon our response and

the policies we enact. Since we know it

is coming, we can prepare. We can curb our

personal spending and accumulate savings.

We have at least a little time to prepare.